This post has been revised and re-published. The original comments are preserved below.

Tuesday, February 16, 2010

Tuesday, February 9, 2010

Lucy was a vegetarian and sapiens an omnivore: Plant foods as natural supplements

Early hominid ancestors like the Australopithecines (e.g., Lucy) were likely strict vegetarians. Meat consumption seems to have occurred at least occasionally among Homo habilis, with more widespread consumption among Homo erectus, and Homo sapiens (i.e., us).

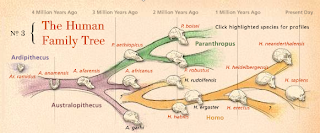

The figure below (from: becominghuman.org; click on it to enlarge) shows a depiction of the human lineage, according to a widely accepted theory developed by Ian Tattersall. As you can see, Neanderthals are on a different branch, and are not believed to have been part of the human lineage.

Does the clear move toward increased meat consumption mean that a meat-only diet is optimal for you?

The answer is “perhaps”; especially if your ancestors were Inuit and you retained their genetic adaptations.

Food specialization tends to increase the chances of extinction of a species, because changes in the environment may lead to the elimination of a single food source, or a limited set of food sources. On a scale from highly specialized to omnivorous, evolution should generally favor adaptations toward the omnivorous end of the scale.

Meat, which naturally comes together with fat, has the advantage of being an energy-dense food. Given this advantage, it is possible that the human species evolved to be exclusively meat eaters, with consumption of plant foods being mostly optional. But this goes somewhat against what we know about evolution.

Consumption of plant matter AND meat – that is, being an omnivore – leads to certain digestive tract adaptations, which would not be present if they were not absolutely necessary. Those adaptations are too costly to be retained without a good reason.

The digestive tract of pure carnivores is usually shorter than that of omnivores. Growing a longer digestive tract and keeping it healthy during a lifetime is a costly proposition.

Let us assume that an ancient human group migrated to a geographical area that forced them to adhere to a particular type of diet, like the ancient Inuit. They would probably have evolved adaptations to that diet. This evolution would not have taken millions of years to occur; it might have taken place in as little as 396 years, if not less.

In spite of divergent adaptations that might have occurred relatively recently (i.e., in the last 100,000 years, after the emergence of our species), among the Inuit for instance, we likely have also species-wide adaptations that make an omnivorous diet generally optimal for most of us.

Meat appears to have many health-promoting and a few unhealthy properties. Plant foods have many health-promoting properties, and thus may act like “natural supplements” to a largely meat-based diet. As Biesalski (2002) put it as part of a discussion of meat and cancer:

“… meat consists of a few, not clearly defined cancer-promoting and a lot of cancer-protecting factors. The latter can be optimized by a diet containing fruit and vegetables, which contain hundreds of more or less proven bioactive constituents, many of them showing antioxidative and anticarcinogenic effects in vitro.”

Reference:

Biesalski, H.K. (2002). Meat and cancer: Meat as a component of a healthy diet. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 56(1), S2-S11.

The figure below (from: becominghuman.org; click on it to enlarge) shows a depiction of the human lineage, according to a widely accepted theory developed by Ian Tattersall. As you can see, Neanderthals are on a different branch, and are not believed to have been part of the human lineage.

Does the clear move toward increased meat consumption mean that a meat-only diet is optimal for you?

The answer is “perhaps”; especially if your ancestors were Inuit and you retained their genetic adaptations.

Food specialization tends to increase the chances of extinction of a species, because changes in the environment may lead to the elimination of a single food source, or a limited set of food sources. On a scale from highly specialized to omnivorous, evolution should generally favor adaptations toward the omnivorous end of the scale.

Meat, which naturally comes together with fat, has the advantage of being an energy-dense food. Given this advantage, it is possible that the human species evolved to be exclusively meat eaters, with consumption of plant foods being mostly optional. But this goes somewhat against what we know about evolution.

Consumption of plant matter AND meat – that is, being an omnivore – leads to certain digestive tract adaptations, which would not be present if they were not absolutely necessary. Those adaptations are too costly to be retained without a good reason.

The digestive tract of pure carnivores is usually shorter than that of omnivores. Growing a longer digestive tract and keeping it healthy during a lifetime is a costly proposition.

Let us assume that an ancient human group migrated to a geographical area that forced them to adhere to a particular type of diet, like the ancient Inuit. They would probably have evolved adaptations to that diet. This evolution would not have taken millions of years to occur; it might have taken place in as little as 396 years, if not less.

In spite of divergent adaptations that might have occurred relatively recently (i.e., in the last 100,000 years, after the emergence of our species), among the Inuit for instance, we likely have also species-wide adaptations that make an omnivorous diet generally optimal for most of us.

Meat appears to have many health-promoting and a few unhealthy properties. Plant foods have many health-promoting properties, and thus may act like “natural supplements” to a largely meat-based diet. As Biesalski (2002) put it as part of a discussion of meat and cancer:

“… meat consists of a few, not clearly defined cancer-promoting and a lot of cancer-protecting factors. The latter can be optimized by a diet containing fruit and vegetables, which contain hundreds of more or less proven bioactive constituents, many of them showing antioxidative and anticarcinogenic effects in vitro.”

Reference:

Biesalski, H.K. (2002). Meat and cancer: Meat as a component of a healthy diet. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 56(1), S2-S11.

Thursday, February 4, 2010

How much vitamin D? Vitamin D Council's recommendations

Since my recent post on problems related to vitamin D deficiency and excess I received several questions. I have also participated in several discussions in other blogs related to vitamin D in the past few days.

There is a lot of consensus about vitamin D deficiency being a problem, but not much about vitamin D in excess being a problem as well.

Some bloggers recommend a lot of supplementation, which may be dangerous because: (a) our body evolved to obtain most of its vitamin D from a combination of sunlight exposure and cholesterol, and thus body accumulation regulation mechanisms are not designed to deal with excessive oral supplementation; and (b) vitamin D, like many fat-soluble vitamins, accumulates in fat tissue over time, and is not easily eliminated by the body when in excess.

The Vitamin D Council has the following general recommendation regarding supplementation:

There is a lot of consensus about vitamin D deficiency being a problem, but not much about vitamin D in excess being a problem as well.

Some bloggers recommend a lot of supplementation, which may be dangerous because: (a) our body evolved to obtain most of its vitamin D from a combination of sunlight exposure and cholesterol, and thus body accumulation regulation mechanisms are not designed to deal with excessive oral supplementation; and (b) vitamin D, like many fat-soluble vitamins, accumulates in fat tissue over time, and is not easily eliminated by the body when in excess.

The Vitamin D Council has the following general recommendation regarding supplementation:

Take an average of 5,000 IU a day, year-round, if you have some sun exposure. If you have little, or no, sun exposure you will need to take at least 5,000 IU per day. How much more depends on your latitude of residence, skin pigmentation, and body weight. Generally speaking, the further you live away from the equator, the darker your skin, and/or the more you weigh, the more you will have to take to maintain healthy blood levels.

They also provide a specific example:

For example, Dr. Cannell lives at latitude 32 degrees, weighs 220 pounds, and has fair skin. In the late fall and winter he takes 5,000 IU per day. In the early fall and spring he takes 2,000 IU per day. In the summer he regularly sunbathes for a few minutes most days and thus takes no vitamin D on those days in the summer.

For those who have problems with supplementation, here is what Dr. Cannell, President of the Vitamin D Council, has to say:

For people who have trouble with supplements, I recommend sunbathing during the warmer months and sun tanning parlors in the colder months. Yes, sun tanning parlors make vitamin D, the most is made by the older type beds. Another possibility is a Sperti vitamin D lamp.

One thing to bear in mind is that if your diet is rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars, you need to change that before you are able to properly manage your vitamin D levels. You need to remove refined carbohydrates and sugars from your diet. No more white bread, bagels, doughnuts, table sugar, sodas sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup; just to name a few of the main culprits.

In fact, a diet rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars, in and of itself, may be one of the reasons of a person''s vitamin D deficiency in the case of appropriate sunlight exposure or dietary intake, and even of excessive levels of vitamin D accumulating in the body in the case of heavy supplementation.

The hormonal responses induced by a diet rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars promote fat deposition and, at the same time, prevent fat degradation. That is, you tend to put on body fat easily, and you tend to have trouble burning that fat.

This causes a "hoarding" effect which leads to an increase in vitamin D stored in the body, and at the same time reduces the levels of vitamin D in circulation. This is because vitamin D is stored in body fat tissue, and has a long half-life, which means that it accumulates (as in a battery) and then slowly gets released into the bloodstream for use, as body fat is used as a source of energy.

It should not be a big surprise that vitamin D deficiency problems correlate strongly with problems associated with heavy consumption of refined carbohydrates and sugars. Both lead to symptoms that are eerily similar; several of which are the symptoms of the metabolic syndrome.

In fact, a diet rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars, in and of itself, may be one of the reasons of a person''s vitamin D deficiency in the case of appropriate sunlight exposure or dietary intake, and even of excessive levels of vitamin D accumulating in the body in the case of heavy supplementation.

The hormonal responses induced by a diet rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars promote fat deposition and, at the same time, prevent fat degradation. That is, you tend to put on body fat easily, and you tend to have trouble burning that fat.

This causes a "hoarding" effect which leads to an increase in vitamin D stored in the body, and at the same time reduces the levels of vitamin D in circulation. This is because vitamin D is stored in body fat tissue, and has a long half-life, which means that it accumulates (as in a battery) and then slowly gets released into the bloodstream for use, as body fat is used as a source of energy.

It should not be a big surprise that vitamin D deficiency problems correlate strongly with problems associated with heavy consumption of refined carbohydrates and sugars. Both lead to symptoms that are eerily similar; several of which are the symptoms of the metabolic syndrome.