Sunday, December 26, 2021

Age-related trends in health markers may indicate survival advantages: The case of platelet counts

Platelets () are particles that circulate in the blood of mammals. They react to blood vessel injuries by forming clots. Platelet counts are provided in standard blood panels, and are used by medical doctors to diagnose possible health problems. At the time of this writing, the refence range for platelet counts is 150,000 to 450,000 per cubic millimeter.

The figure below has two graphs, and is based on an article by Balduini and Noris, published in 2014 in the prestigious journal Haematologica (). The graph on the left shows the distribution of platelet counts by age and sex. The one on the right shows the reference ranges for platelet counts by age and sex.

The reference ranges within the bars include all individuals in the same age-sex group, whereas the ones outside the bars are based on groups of individuals in specific areas (i.e., geographic regions) where the age-sex reference ranges are wider. A reference range is essentially an interval, derived from statistical analyses, in which one would expect individuals who are disease-free to fall into.

A clear pattern that emerges from these graphs is that platelet counts go down with age, in both men and women. A tendency to form clots is generally associated with health problems at more advanced ages, even though blood clotting is necessary for good health. Given this, one could interpret the graphs as indicating that older individuals have lower blood clot counts because those lower counts are associated with a survival advantage.

This interpretation is not guaranteed to be correct, of course. Nevertheless, one of the key conclusions by the authors of the study seems quite correct: “[…] using 150–400×10^9/L as the normal range for platelet count, a number of old people of some areas could be at risk of receiving a wrong diagnosis of thrombocytopenia, while young inhabitants of other areas could be at risk of an undue diagnosis of thrombocytosis.”

If you get a platelet count in a standard blood panel that is out of the reference range, your doctor may tell you that this could be an indication of a frightening underlying health problem. If this happens, you may want to discuss this blog post, and the article on which it is based, with your doctor. There are follow-up tests that can rule out serious underlying problems. Having said that, a low count may in fact be a good sign.

Sunday, October 24, 2021

You can eat a lot during the Holiday Season and gain no body fat, as long as you also eat little

The evolutionary pressures placed by periods of famine shaped the physiology of most animals, including humans, toward a design that favors asymmetric food consumption. That is, most animals are “designed” to alternate between eating little and then a lot.

Often when people hear this argument they point out the obvious. There is no evidence that our ancestors were constantly starving. This is correct, but what these folks seem to forget is that evolution responds to events that alter reproductive success rates (), even if those events are rare.

If an event causes a significant amount of death but occurs only once every year, a population will still evolve traits in response to the event. Food scarcity is one such type of event.

Since evolution is blind to complexity, adaptations to food scarcity can take all shapes and forms, including counterintuitive ones. Complicating this picture is the fact that food does not only provide us with fuel, but also with the sources of important structural components, signaling elements (e.g., hormones), and process catalysts (e.g., enzymes).

In other words, we may have traits that are health-promoting under conditions of food scarcity, but those traits are only likely to benefit our health as long as food scarcity is relatively short-term. Not eating anything for 40 days would be lethal for most people.

By "eating little" I don’t mean necessarily fasting. Given the amounts of mucus and dead cells (from normal cell turnover) passing through the digestive tract, it is very likely that we’ll be always digesting something. So eating very little within a period of 10 hours sends the body a message that is similar to the message sent by eating nothing within the same period of 10 hours.

Most of the empirical research that I've reviewed suggests that eating very little within a period of, say, 10-20 hours and then eating to satisfaction in one single meal will elicit the following responses. Protein phosphorylation underlies many of them.

- Your body will hold on to its most important nutrient reserves when you eat little, using selective autophagy to generate energy (, ). This may have powerful health-promoting properties, including the effect of triggering anti-cancer mechanisms.

- Food will taste fantastic when you feast, to such an extent that this effect will be much stronger than that associated with any spice ().

- Nutrients will be allocated more effectively when you feast, leading to a lower net gain of body fat ().

- The caloric value of food will be decreased, with a 14 percent decrease being commonly found in the literature ().

- The feast will prevent your body from down-regulating your metabolism via subclinical hypothyroidism (), which often happens when the period in which one eats little extends beyond a certain threshold (e.g., more than one week).

- Your mood will be very cheerful when you feast, potentially improving social relationships. That is, if you don’t become too grouchy during the period in which you eat little.

I recall once participating in a meeting that went from early morning to late afternoon. We had the option of taking a lunch break, or working through lunch and ending the meeting earlier. Not only was I the only person to even consider the second option, some people thought that the idea of skipping lunch was outrageous, with a few implying that they would have headaches and other problems.

When I said that I had had nothing for breakfast, a few thought that I was pushing my luck. One of my colleagues warned me that I might be damaging my health irreparably by doing those things. Well, maybe they were right on both grounds, who knows?

It is my belief that the vast majority of humans will do quite fine if they eat little or nothing for a period of 20 hours. The problem is that they need to be convinced first that they have nothing to worry about. Otherwise they may end up with a headache or worse, entirely due to psychological mechanisms ().

There is no need to eat beyond satiety when you feast. I’d recommend that you just eat to satiety, and don’t force yourself to eat more than that. If you avoid industrialized foods when you feast, that will be even better, because satiety will be achieved faster. One of the main characteristics of industrialized foods is that they promote unnatural overeating; congrats food engineers on a job well done!

If you are relatively lean, satiety will normally be achieved with less food than if you are not. Hunger intensity and duration tends to be generally associated with body weight. Except for dedicated bodybuilders and a few other athletes, body weight gain is much more strongly influenced by body fat gain than by muscle gain.

Sunday, September 19, 2021

Dietary protein does not become body fat if you are on a low carbohydrate diet

By definition LC is about dietary carbohydrate restriction. If you are reducing carbohydrates, your proportional intake of protein or fat, or both, will go up. While I don’t think there is anything wrong with a high fat diet, it seems to me that the true advantage of LC may be in how protein is allocated, which appears to contribute to a better body composition.

LC with more animal protein and less fat makes particularly good sense to me. Eating a variety of unprocessed animal foods, as opposed to only muscle meat from grain-fed cattle, will get you that. In simple terms, LC with more protein, achieved in a natural way with unprocessed foods, means more of the following in one's diet: lean meats, seafood and vegetables. Possibly with lean meats and seafood making up more than half of one’s protein intake. Generally speaking, large predatory fish species (e.g., various shark species, including dogfish) are better avoided to reduce exposure to toxic metals.

Organ meats such as beef liver are also high in protein and low in fat, but should be consumed in moderation due to the risk of hypervitaminosis; particularly hypervitaminosis A. Our ancestors ate the animal whole, and organ mass makes up about 10-20 percent of total mass in ruminants. Eating organ meats once a week places you approximately within that range.

In LC liver glycogen is regularly depleted, so the amino acids resulting from the digestion of protein will be primarily used to replenish liver glycogen, to replenish the albumin pool, for oxidation, and various other processes (e.g., tissue repair, hormone production). If you do some moderate weight training, some of those amino acids will be used for muscle repair and potentially growth.

In this sense, the true “metabolic advantage” of LC, so to speak, comes from protein and not fat. “Calories in” still counts, but you get better allocation of nutrients. Moreover, in LC, the calorie value of protein goes down a bit, because your body is using it as a “jack of all trades”, and thus in a less efficient way. This renders protein the least calorie-dense macronutrient, yielding fewer calories per gram than carbohydrates; and significantly fewer calories per gram when compared with dietary fat and alcohol.

Dietary fat is easily stored as body fat after digestion. In LC, it is difficult for the body to store amino acids as body fat. The only path would be conversion to glucose and uptake by body fat cells, but in LC the liver will typically be starving and want all the extra glucose for itself, so that it can feed its ultimate master – the brain. The liver glycogen depletion induced by LC creates a hormonal mix that places the body in fat release mode, making it difficult for fat cells to take up glucose via the GLUT4 transporter protein.

Excess amino acids are oxidized for energy. This may be why many people feel a slight surge of energy after a high-protein meal. (A related effect is associated with alcohol consumption, which is often masked by the relaxing effect also associated with alcohol consumption.) Amino acid oxidation is not associated with cancer. Neither is fat oxidation. But glucose oxidation is; this is known as the Warburg effect.

A high-protein LC approach will not work very well for athletes who deplete major amounts of muscle glycogen as part of their daily training regimens. These folks will invariably need more carbohydrates to keep their performance levels up. Ultimately this is a numbers game. The protein-to-glucose conversion rate is about 2-to-1. If an athlete depletes 300 g of muscle glycogen per day, he or she will need about 600 g of protein to replenish that based only on protein. This is too high an intake of protein by any standard.

A recreational exerciser who depletes 60 g of glycogen 3 times per week can easily replenish that muscle glycogen with dietary protein. Someone who exercises with weights for 40 minutes 3 times per week will deplete about that much glycogen each time. Contrary to popular belief, muscle glycogen is only minimally replenished postprandially (i.e., after meals) based on dietary sources. Liver glycogen replenishment is prioritized postprandially. Muscle glycogen is replenished over several days, primarily based on liver glycogen. It is one fast-filling tank replenishing another slow-filling one.

Recreational exercisers who are normoglycemic and who do LC intermittently tend to increase the size of their liver glycogen tank over time, via compensatory adaptation, and also use more fat (and ketones, which are byproducts of fat metabolism) as sources of energy. Somewhat paradoxically, these folks benefit from regular high carbohydrate intake days (e.g., once a week, or on exercise days), since their liver glycogen tanks will typically store more glycogen. If they keep their liver and muscle glycogen tanks half empty all the time, compensatory adaptation suggests that both their liver and muscle glycogen tanks will over time become smaller, and that their muscles will store more fat.

One way or another, with the exception of those with major liver insulin resistance, dietary protein does not become body fat if you are on a LC diet.

LC with more animal protein and less fat makes particularly good sense to me. Eating a variety of unprocessed animal foods, as opposed to only muscle meat from grain-fed cattle, will get you that. In simple terms, LC with more protein, achieved in a natural way with unprocessed foods, means more of the following in one's diet: lean meats, seafood and vegetables. Possibly with lean meats and seafood making up more than half of one’s protein intake. Generally speaking, large predatory fish species (e.g., various shark species, including dogfish) are better avoided to reduce exposure to toxic metals.

Organ meats such as beef liver are also high in protein and low in fat, but should be consumed in moderation due to the risk of hypervitaminosis; particularly hypervitaminosis A. Our ancestors ate the animal whole, and organ mass makes up about 10-20 percent of total mass in ruminants. Eating organ meats once a week places you approximately within that range.

In LC liver glycogen is regularly depleted, so the amino acids resulting from the digestion of protein will be primarily used to replenish liver glycogen, to replenish the albumin pool, for oxidation, and various other processes (e.g., tissue repair, hormone production). If you do some moderate weight training, some of those amino acids will be used for muscle repair and potentially growth.

In this sense, the true “metabolic advantage” of LC, so to speak, comes from protein and not fat. “Calories in” still counts, but you get better allocation of nutrients. Moreover, in LC, the calorie value of protein goes down a bit, because your body is using it as a “jack of all trades”, and thus in a less efficient way. This renders protein the least calorie-dense macronutrient, yielding fewer calories per gram than carbohydrates; and significantly fewer calories per gram when compared with dietary fat and alcohol.

Dietary fat is easily stored as body fat after digestion. In LC, it is difficult for the body to store amino acids as body fat. The only path would be conversion to glucose and uptake by body fat cells, but in LC the liver will typically be starving and want all the extra glucose for itself, so that it can feed its ultimate master – the brain. The liver glycogen depletion induced by LC creates a hormonal mix that places the body in fat release mode, making it difficult for fat cells to take up glucose via the GLUT4 transporter protein.

Excess amino acids are oxidized for energy. This may be why many people feel a slight surge of energy after a high-protein meal. (A related effect is associated with alcohol consumption, which is often masked by the relaxing effect also associated with alcohol consumption.) Amino acid oxidation is not associated with cancer. Neither is fat oxidation. But glucose oxidation is; this is known as the Warburg effect.

A recreational exerciser who depletes 60 g of glycogen 3 times per week can easily replenish that muscle glycogen with dietary protein. Someone who exercises with weights for 40 minutes 3 times per week will deplete about that much glycogen each time. Contrary to popular belief, muscle glycogen is only minimally replenished postprandially (i.e., after meals) based on dietary sources. Liver glycogen replenishment is prioritized postprandially. Muscle glycogen is replenished over several days, primarily based on liver glycogen. It is one fast-filling tank replenishing another slow-filling one.

Recreational exercisers who are normoglycemic and who do LC intermittently tend to increase the size of their liver glycogen tank over time, via compensatory adaptation, and also use more fat (and ketones, which are byproducts of fat metabolism) as sources of energy. Somewhat paradoxically, these folks benefit from regular high carbohydrate intake days (e.g., once a week, or on exercise days), since their liver glycogen tanks will typically store more glycogen. If they keep their liver and muscle glycogen tanks half empty all the time, compensatory adaptation suggests that both their liver and muscle glycogen tanks will over time become smaller, and that their muscles will store more fat.

One way or another, with the exception of those with major liver insulin resistance, dietary protein does not become body fat if you are on a LC diet.

Sunday, August 15, 2021

The China Study one more time: Are raw plant foods giving people cancer?

In this previous post I analyzed some data from the China Study that included counties where there were cases of schistosomiasis infection. Following one of Denise Minger’s suggestions, I removed all those counties from the data. I was left with 29 counties, a much smaller sample size. I then ran a multivariate analysis using WarpPLS (warppls.com), like in the previous post, but this time I used an algorithm that identifies nonlinear relationships between variables.

Below is the model with the results. (Click on it to enlarge. Use the "CRTL" and "+" keys to zoom in, and CRTL" and "-" to zoom out.) As in the previous post, the arrows explore associations between variables. The variables are shown within ovals. The meaning of each variable is the following: aprotein = animal protein consumption; pprotein = plant protein consumption; cholest = total cholesterol; crcancer = colorectal cancer.

What is total cholesterol doing at the right part of the graph? It is there because I am analyzing the associations between animal protein and plant protein consumption with colorectal cancer, controlling for the possible confounding effect of total cholesterol.

I am not hypothesizing anything regarding total cholesterol, even though this variable is shown as pointing at colorectal cancer. I am just controlling for it. This is the type of thing one can do in multivariate analyzes. This is how you “control for the effect of a variable” in an analysis like this.

ins Since the sample is fairly small, we end up with nonsignificant beta coefficients that would normally be statistically significant with a larger sample. But it helps that we are using nonparametric statistics, because they are still robust in the presence of small samples, and deviations from normality. Also the nonlinear algorithm is more sensitive to relationships that do not fit a classic linear pattern. We can summarize the findings as follows:

- As animal protein consumption increases, plant protein consumption decreases significantly (beta=-0.36; P<0.01). This is to be expected and helpful in the analysis, as it differentiates somewhat animal from plant protein consumers. Those folks who got more of their protein from animal foods tended to get significantly less protein from plant foods.

- As animal protein consumption increases, colorectal cancer decreases, but not in a statistically significant way (beta=-0.31; P=0.10). The beta here is certainly high, and the likelihood that the relationship is real is 90 percent, even with such a small sample.

- As plant protein consumption increases, colorectal cancer increases significantly (beta=0.47; P<0.01). The small sample size was not enough to make this association nonsignificant. The reason is that the distribution pattern of the data here is very indicative of a real association, which is reflected in the low P value.

Remember, these results are not confounded by schistosomiasis infection, because we are only looking at counties where there were no cases of schistosomiasis infection. These results are not confounded by total cholesterol either, because we controlled for that possible confounding effect. Now, control variable or not, you would be correct to point out that the association between total cholesterol and colorectal cancer is high (beta=0.58; P=0.01). So let us take a look at the shape of that association:

Does this graph remind you of the one on this post; the one with several U curves? Yes. And why is that? Maybe it reflects a tendency among the folks who had low cholesterol to have more cancer because the body needs cholesterol to fight disease, and cancer is a disease. And maybe it reflects a tendency among the folks who have high total cholesterol to do so because total cholesterol (and particularly its main component, LDL cholesterol) is in part a marker of disease, and cancer is often a culmination of various metabolic disorders (e.g., the metabolic syndrome) that are nothing but one disease after another.

To believe that total cholesterol causes colorectal cancer is nonsensical because total cholesterol is generally increased by consumption of animal products, of which animal protein consumption is a proxy. (In this reduced dataset, the linear univariate correlation between animal protein consumption and total cholesterol is a significant and positive 0.36.) And animal protein consumption seems to be protective again colorectal cancer in this dataset (negative association on the model graph).

Now comes the part that I find the most ironic about this whole discussion in the blogosphere that has been going on recently about the China Study; and the answer to the question posed in the title of this post: Are raw plant foods giving people cancer? If you think that the answer is “yes”, think again. The variable that is strongly associated with colorectal cancer is plant protein consumption.

Do fruits, veggies, and other plant foods that can be consumed raw have a lot of protein?

With a few exceptions, like nuts, they do not. Most raw plant foods have trace amounts of protein, especially when compared with foods made from refined grains and seeds (e.g., wheat grains, soybean seeds). So the contribution of raw fruits and veggies in general could not have influenced much the variable plant protein consumption. To put this in perspective, the average plant protein consumption per day in this dataset was 63 g; even if they were eating 30 bananas a day, the study participants would not get half that much protein from bananas.

Refined foods made from grains and seeds are made from those plant parts that the plants absolutely do not “want” animals to eat. They are the plants’ “children” or “children’s nutritional reserves”, so to speak. This is why they are packed with nutrients, including protein and carbohydrates, but also often toxic and/or unpalatable to animals (including humans) when eaten raw.

But humans are so smart; they learned how to industrially refine grains and seeds for consumption. The resulting human-engineered products (usually engineered to sell as many units as possible, not to make you healthy) normally taste delicious, so you tend to eat a lot of them. They also tend to raise blood sugar to abnormally high levels, because industrial refining makes their high carbohydrate content easily digestible. Refined foods made from grains and seeds also tend to cause leaky gut problems, and autoimmune disorders like celiac disease. Yep, we humans are really smart.

Thanks again to Dr. Campbell and his colleagues for collecting and compiling the China Study data, and to Ms. Minger for making the data available in easily downloadable format and for doing some superb analyses herself.

Below is the model with the results. (Click on it to enlarge. Use the "CRTL" and "+" keys to zoom in, and CRTL" and "-" to zoom out.) As in the previous post, the arrows explore associations between variables. The variables are shown within ovals. The meaning of each variable is the following: aprotein = animal protein consumption; pprotein = plant protein consumption; cholest = total cholesterol; crcancer = colorectal cancer.

What is total cholesterol doing at the right part of the graph? It is there because I am analyzing the associations between animal protein and plant protein consumption with colorectal cancer, controlling for the possible confounding effect of total cholesterol.

I am not hypothesizing anything regarding total cholesterol, even though this variable is shown as pointing at colorectal cancer. I am just controlling for it. This is the type of thing one can do in multivariate analyzes. This is how you “control for the effect of a variable” in an analysis like this.

ins Since the sample is fairly small, we end up with nonsignificant beta coefficients that would normally be statistically significant with a larger sample. But it helps that we are using nonparametric statistics, because they are still robust in the presence of small samples, and deviations from normality. Also the nonlinear algorithm is more sensitive to relationships that do not fit a classic linear pattern. We can summarize the findings as follows:

- As animal protein consumption increases, plant protein consumption decreases significantly (beta=-0.36; P<0.01). This is to be expected and helpful in the analysis, as it differentiates somewhat animal from plant protein consumers. Those folks who got more of their protein from animal foods tended to get significantly less protein from plant foods.

- As animal protein consumption increases, colorectal cancer decreases, but not in a statistically significant way (beta=-0.31; P=0.10). The beta here is certainly high, and the likelihood that the relationship is real is 90 percent, even with such a small sample.

- As plant protein consumption increases, colorectal cancer increases significantly (beta=0.47; P<0.01). The small sample size was not enough to make this association nonsignificant. The reason is that the distribution pattern of the data here is very indicative of a real association, which is reflected in the low P value.

Remember, these results are not confounded by schistosomiasis infection, because we are only looking at counties where there were no cases of schistosomiasis infection. These results are not confounded by total cholesterol either, because we controlled for that possible confounding effect. Now, control variable or not, you would be correct to point out that the association between total cholesterol and colorectal cancer is high (beta=0.58; P=0.01). So let us take a look at the shape of that association:

Does this graph remind you of the one on this post; the one with several U curves? Yes. And why is that? Maybe it reflects a tendency among the folks who had low cholesterol to have more cancer because the body needs cholesterol to fight disease, and cancer is a disease. And maybe it reflects a tendency among the folks who have high total cholesterol to do so because total cholesterol (and particularly its main component, LDL cholesterol) is in part a marker of disease, and cancer is often a culmination of various metabolic disorders (e.g., the metabolic syndrome) that are nothing but one disease after another.

To believe that total cholesterol causes colorectal cancer is nonsensical because total cholesterol is generally increased by consumption of animal products, of which animal protein consumption is a proxy. (In this reduced dataset, the linear univariate correlation between animal protein consumption and total cholesterol is a significant and positive 0.36.) And animal protein consumption seems to be protective again colorectal cancer in this dataset (negative association on the model graph).

Now comes the part that I find the most ironic about this whole discussion in the blogosphere that has been going on recently about the China Study; and the answer to the question posed in the title of this post: Are raw plant foods giving people cancer? If you think that the answer is “yes”, think again. The variable that is strongly associated with colorectal cancer is plant protein consumption.

Do fruits, veggies, and other plant foods that can be consumed raw have a lot of protein?

With a few exceptions, like nuts, they do not. Most raw plant foods have trace amounts of protein, especially when compared with foods made from refined grains and seeds (e.g., wheat grains, soybean seeds). So the contribution of raw fruits and veggies in general could not have influenced much the variable plant protein consumption. To put this in perspective, the average plant protein consumption per day in this dataset was 63 g; even if they were eating 30 bananas a day, the study participants would not get half that much protein from bananas.

Refined foods made from grains and seeds are made from those plant parts that the plants absolutely do not “want” animals to eat. They are the plants’ “children” or “children’s nutritional reserves”, so to speak. This is why they are packed with nutrients, including protein and carbohydrates, but also often toxic and/or unpalatable to animals (including humans) when eaten raw.

But humans are so smart; they learned how to industrially refine grains and seeds for consumption. The resulting human-engineered products (usually engineered to sell as many units as possible, not to make you healthy) normally taste delicious, so you tend to eat a lot of them. They also tend to raise blood sugar to abnormally high levels, because industrial refining makes their high carbohydrate content easily digestible. Refined foods made from grains and seeds also tend to cause leaky gut problems, and autoimmune disorders like celiac disease. Yep, we humans are really smart.

Thanks again to Dr. Campbell and his colleagues for collecting and compiling the China Study data, and to Ms. Minger for making the data available in easily downloadable format and for doing some superb analyses herself.

Labels:

cancer,

China Study,

J curve,

multivariate analysis,

refined carbs,

research,

statistics,

U curve,

warppls

Tuesday, June 22, 2021

Blood glucose control before age 55 may increase your chances of living beyond 90

This post refers to an interesting study by Yashin and colleagues (2009) at Duke University’s Center for Population Health and Aging. (The full reference to the article, and a link, are at the end of this post.) This study is a gem with some rough edges, and some interesting implications.

The study uses data from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS). The FHS, which started in the late 1940s, recruited 5209 healthy participants (2336 males and 2873 females), aged 28 to 62, in the town of Framingham, Massachusetts. At the time of Yashin and colleagues’ article publication, there were 993 surviving participants.

I rearranged figure 2 from the Yashin and colleagues article so that the two graphs (for females and males) appeared one beside the other. The result is shown below (click on it to enlarge); the caption at the bottom-right corner refers to both graphs. The figure shows the age-related trajectory of blood glucose levels, grouped by lifespan (LS), starting at age 40.

As you can see from the figure above, blood glucose levels increase with age, even for long-lived individuals (LS > 90). The increases follow a U-curve (a.k.a. J-curve) pattern; the beginning of the right side of a U curve, to be more precise. The main difference in the trajectories of the blood glucose levels is that as lifespan increases, so does the width of the U curve. In other words, in long-lived people, blood glucose increases slowly with age; particularly up to 55 years of age, when it starts increasing more rapidly.

Now, here is one of the rough edges of this study. The authors do not provide standard deviations. You can ignore the error bars around the points on the graph; they are not standard deviations. They are standard errors, which are much lower than the corresponding standard deviations. Standard errors are calculated by dividing the standard deviations by the square root of the sample sizes for each trajectory point (which the authors do not provide either), so they go up with age since progressively smaller numbers of individuals reach advanced ages.

So, no need to worry if your blood glucose levels are higher than those shown on the vertical axes of the graphs. (I will comment more on those numbers below.) Not everybody who lived beyond 90 had a blood glucose of around 80 mg/dl at age 40. I wouldn't be surprised if about 2/3 of the long-lived participants had blood glucose levels in the range of 65 to 95 at that age.

Here is another rough edge. It is pretty clear that the authors’ main independent variable (i.e., health predictor) in this study is average blood glucose, which they refer to simply as “blood glucose”. However, the measure of blood glucose in the FHS is a very rough estimation of average blood glucose, because they measured blood glucose levels at random times during the day. These measurements, when averaged, are closer to fasting blood glucose levels than to average blood glucose levels.

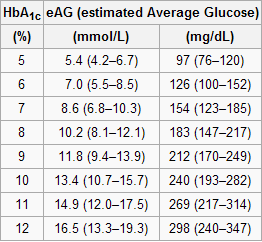

A more reliable measure of average blood glucose levels is that of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). Blood glucose glycates (i.e., sticks to, like most sugary substances) hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells. Since red blood cells are relatively long-lived, with a turnover of about 3 months, HbA1c (given in percentages) is a good indicator of average blood glucose levels (if you don’t suffer from anemia or a few other blood abnormalities). Based on HbA1c, one can then estimate his or her average blood glucose level for the previous 3 months before the test, using one of the following equations, depending on whether the measurement is in mg/dl or mmol/l.

Average blood glucose (mg/dl) = 28.7 × HbA1c − 46.7

Average blood glucose (mmol/l) = 1.59 × HbA1c − 2.59

The table below, from Wikipedia, shows average blood glucose levels corresponding to various HbA1c values. As you can see, they are generally higher than the corresponding fasting blood glucose levels would normally be (the latter is what the values on the vertical axes of the graphs above from Yashin and colleagues’ study roughly measure). This is to be expected, because blood glucose levels vary a lot during the day, and are often transitorily high in response to food intake and fluctuations in various hormones. Growth hormone, cortisol and noradrenaline are examples of hormones that increase blood glucose. Only one hormone effectively decreases blood glucose levels, insulin, by stimulating glucose uptake and storage as glycogen and fat.

Nevertheless, one can reasonably expect fasting blood glucose levels to have been highly correlated with average blood glucose levels in the sample. So, in my opinion, the graphs above showing age-related blood glucose trajectories are still valid, in terms of their overall shape, but the values on the vertical axes should have been measured differently, perhaps using the formulas above.

Ironically, those who achieve low average blood glucose levels (measured based on HbA1c) by adopting a low carbohydrate diet (one of the most effective ways) frequently have somewhat high fasting blood glucose levels because of physiological (or benign) insulin resistance. Their body is primed to burn fat for energy, not glucose. Thus when growth hormone levels spike in the morning, so do blood glucose levels, as muscle cells are in glucose rejection mode. This is a benign version of the dawn effect (a.k.a. dawn phenomenon), which happens with quite a few low carbohydrate dieters, particularly with those who are deep in ketosis at dawn.

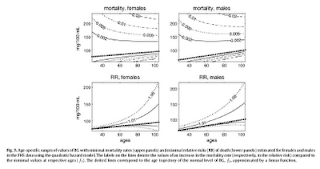

Yashin and colleagues also modeled relative risk of death based on blood glucose levels, using a fairly sophisticated mathematical model that takes into consideration U-curve relationships. What they found is intuitively appealing, and is illustrated by the two graphs at the bottom of the figure below. The graphs show how the relative risks (e.g., 1.05, on the topmost dashed line on the both graphs) associated with various ranges of blood glucose levels vary with age, for both females and males.

What the graphs above are telling us is that once you reach old age, controlling for blood sugar levels is not as effective as doing it earlier, because you are more likely to die from what the authors refer to as “other causes”. For example, at the age of 90, having a blood glucose of 150 mg/dl (corrected for the measurement problem noted earlier, this would be perhaps 165 mg/dl, from HbA1c values) is likely to increase your risk of death by only 5 percent. The graphs account for the facts that: (a) blood glucose levels naturally increase with age, and (b) fewer people survive as age progresses. So having that level of blood glucose at age 60 would significantly increase relative risk of death at that age; this is not shown on the graph, but can be inferred.

Here is a final rough edge of this study. From what I could gather from the underlying equations, the relative risks shown above do not account for the effect of high blood glucose levels earlier in life on relative risk of death later in life. This is a problem, even though it does not completely invalidate the conclusion above. As noted by several people (including Gary Taubes in his book Good Calories, Bad Calories), many of the diseases associated with high blood sugar levels (e.g., cancer) often take as much as 20 years of high blood sugar levels to develop. So the relative risks shown above underestimate the effect of high blood glucose levels earlier in life.

Do the long-lived participants have some natural protection against accelerated increases in blood sugar levels, or was it their diet and lifestyle that protected them? This question cannot be answered based on the study.

Assuming that their diet and lifestyle protected them, it is reasonable to argue that: (a) if you start controlling your average blood sugar levels well before you reach the age of 55, you may significantly increase your chances of living beyond the age of 90; (b) it is likely that your blood glucose levels will go up with age, but if you can manage to slow down that progression, you will increase your chances of living a longer and healthier life; (c) you should focus your control on reliable measures of average blood glucose levels, such as HbA1c, not fasting blood glucose levels (postprandial glucose levels are also a good option, because they contribute a lot to HbA1c increases); and (d) it is never too late to start controlling your blood glucose levels, but the more you wait, the bigger is the risk.

References:

Taubes, G. (2007). Good calories, bad calories: Challenging the conventional wisdom on diet, weight control, and disease. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Yashin, A.I., Ukraintseva, S.V., Arbeev, K.G., Akushevich, I., Arbeeva, L.S., & Kulminski, A.M. (2009). Maintaining physiological state for exceptional survival: What is the normal level of blood glucose and does it change with age? Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 130(9), 611-618.

The study uses data from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS). The FHS, which started in the late 1940s, recruited 5209 healthy participants (2336 males and 2873 females), aged 28 to 62, in the town of Framingham, Massachusetts. At the time of Yashin and colleagues’ article publication, there were 993 surviving participants.

I rearranged figure 2 from the Yashin and colleagues article so that the two graphs (for females and males) appeared one beside the other. The result is shown below (click on it to enlarge); the caption at the bottom-right corner refers to both graphs. The figure shows the age-related trajectory of blood glucose levels, grouped by lifespan (LS), starting at age 40.

As you can see from the figure above, blood glucose levels increase with age, even for long-lived individuals (LS > 90). The increases follow a U-curve (a.k.a. J-curve) pattern; the beginning of the right side of a U curve, to be more precise. The main difference in the trajectories of the blood glucose levels is that as lifespan increases, so does the width of the U curve. In other words, in long-lived people, blood glucose increases slowly with age; particularly up to 55 years of age, when it starts increasing more rapidly.

Now, here is one of the rough edges of this study. The authors do not provide standard deviations. You can ignore the error bars around the points on the graph; they are not standard deviations. They are standard errors, which are much lower than the corresponding standard deviations. Standard errors are calculated by dividing the standard deviations by the square root of the sample sizes for each trajectory point (which the authors do not provide either), so they go up with age since progressively smaller numbers of individuals reach advanced ages.

So, no need to worry if your blood glucose levels are higher than those shown on the vertical axes of the graphs. (I will comment more on those numbers below.) Not everybody who lived beyond 90 had a blood glucose of around 80 mg/dl at age 40. I wouldn't be surprised if about 2/3 of the long-lived participants had blood glucose levels in the range of 65 to 95 at that age.

Here is another rough edge. It is pretty clear that the authors’ main independent variable (i.e., health predictor) in this study is average blood glucose, which they refer to simply as “blood glucose”. However, the measure of blood glucose in the FHS is a very rough estimation of average blood glucose, because they measured blood glucose levels at random times during the day. These measurements, when averaged, are closer to fasting blood glucose levels than to average blood glucose levels.

A more reliable measure of average blood glucose levels is that of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). Blood glucose glycates (i.e., sticks to, like most sugary substances) hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells. Since red blood cells are relatively long-lived, with a turnover of about 3 months, HbA1c (given in percentages) is a good indicator of average blood glucose levels (if you don’t suffer from anemia or a few other blood abnormalities). Based on HbA1c, one can then estimate his or her average blood glucose level for the previous 3 months before the test, using one of the following equations, depending on whether the measurement is in mg/dl or mmol/l.

Average blood glucose (mg/dl) = 28.7 × HbA1c − 46.7

Average blood glucose (mmol/l) = 1.59 × HbA1c − 2.59

The table below, from Wikipedia, shows average blood glucose levels corresponding to various HbA1c values. As you can see, they are generally higher than the corresponding fasting blood glucose levels would normally be (the latter is what the values on the vertical axes of the graphs above from Yashin and colleagues’ study roughly measure). This is to be expected, because blood glucose levels vary a lot during the day, and are often transitorily high in response to food intake and fluctuations in various hormones. Growth hormone, cortisol and noradrenaline are examples of hormones that increase blood glucose. Only one hormone effectively decreases blood glucose levels, insulin, by stimulating glucose uptake and storage as glycogen and fat.

Nevertheless, one can reasonably expect fasting blood glucose levels to have been highly correlated with average blood glucose levels in the sample. So, in my opinion, the graphs above showing age-related blood glucose trajectories are still valid, in terms of their overall shape, but the values on the vertical axes should have been measured differently, perhaps using the formulas above.

Ironically, those who achieve low average blood glucose levels (measured based on HbA1c) by adopting a low carbohydrate diet (one of the most effective ways) frequently have somewhat high fasting blood glucose levels because of physiological (or benign) insulin resistance. Their body is primed to burn fat for energy, not glucose. Thus when growth hormone levels spike in the morning, so do blood glucose levels, as muscle cells are in glucose rejection mode. This is a benign version of the dawn effect (a.k.a. dawn phenomenon), which happens with quite a few low carbohydrate dieters, particularly with those who are deep in ketosis at dawn.

Yashin and colleagues also modeled relative risk of death based on blood glucose levels, using a fairly sophisticated mathematical model that takes into consideration U-curve relationships. What they found is intuitively appealing, and is illustrated by the two graphs at the bottom of the figure below. The graphs show how the relative risks (e.g., 1.05, on the topmost dashed line on the both graphs) associated with various ranges of blood glucose levels vary with age, for both females and males.

What the graphs above are telling us is that once you reach old age, controlling for blood sugar levels is not as effective as doing it earlier, because you are more likely to die from what the authors refer to as “other causes”. For example, at the age of 90, having a blood glucose of 150 mg/dl (corrected for the measurement problem noted earlier, this would be perhaps 165 mg/dl, from HbA1c values) is likely to increase your risk of death by only 5 percent. The graphs account for the facts that: (a) blood glucose levels naturally increase with age, and (b) fewer people survive as age progresses. So having that level of blood glucose at age 60 would significantly increase relative risk of death at that age; this is not shown on the graph, but can be inferred.

Here is a final rough edge of this study. From what I could gather from the underlying equations, the relative risks shown above do not account for the effect of high blood glucose levels earlier in life on relative risk of death later in life. This is a problem, even though it does not completely invalidate the conclusion above. As noted by several people (including Gary Taubes in his book Good Calories, Bad Calories), many of the diseases associated with high blood sugar levels (e.g., cancer) often take as much as 20 years of high blood sugar levels to develop. So the relative risks shown above underestimate the effect of high blood glucose levels earlier in life.

Do the long-lived participants have some natural protection against accelerated increases in blood sugar levels, or was it their diet and lifestyle that protected them? This question cannot be answered based on the study.

Assuming that their diet and lifestyle protected them, it is reasonable to argue that: (a) if you start controlling your average blood sugar levels well before you reach the age of 55, you may significantly increase your chances of living beyond the age of 90; (b) it is likely that your blood glucose levels will go up with age, but if you can manage to slow down that progression, you will increase your chances of living a longer and healthier life; (c) you should focus your control on reliable measures of average blood glucose levels, such as HbA1c, not fasting blood glucose levels (postprandial glucose levels are also a good option, because they contribute a lot to HbA1c increases); and (d) it is never too late to start controlling your blood glucose levels, but the more you wait, the bigger is the risk.

References:

Taubes, G. (2007). Good calories, bad calories: Challenging the conventional wisdom on diet, weight control, and disease. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

Yashin, A.I., Ukraintseva, S.V., Arbeev, K.G., Akushevich, I., Arbeeva, L.S., & Kulminski, A.M. (2009). Maintaining physiological state for exceptional survival: What is the normal level of blood glucose and does it change with age? Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 130(9), 611-618.

Thursday, March 11, 2021

The steep obesity increase in the USA in the 1980s: In a sense, it reflects a major success story

Obesity rates have increased in the USA over the years, but the steep increase starting around the 1980s is unusual. Wang and Beydoun do a good job at discussing this puzzling phenomenon (), and a blog post by Discover Magazine provides a graph (see below) that clear illustrates it ().

What is the reason for this?

You may be tempted to point at increases in calorie intake and/or changes in macronutrient composition, but neither can explain this sharp increase in obesity in the 1980s. The differences in calorie intake and macronutrient composition are simply not large enough to fully account for such a steep increase. And the data is actually full of oddities.

For example, an article by Austin and colleagues (which ironically blames calorie consumption for the obesity epidemic) suggests that obese men in a NHANES (2005–2006) sample consumed only 2.2 percent more calories per day on average than normal weight men in a NHANES I (1971–1975) sample ().

So, what could be the main reason for the steep increase in obesity prevalence since the 1980s?

The first clue comes from an interesting observation. If you age-adjust obesity trends (by controlling for age), you end up with a much less steep increase. The steep increase in the graph above is based on raw, unadjusted numbers. There is a higher prevalence of obesity among older people (no surprise here). And older people are people that have survived longer than younger people. (Don’t be too quick to say “duh” just yet.)

This age-obesity connection also reflects an interesting difference between humans living “in the wild” and those who do not, which becomes more striking when we compare hunter-gatherers with modern urbanites. Adult hunter-gatherers, unlike modern urbanites, do not gain weight as they age; they actually lose weight (, ).

Modern urbanites gain a significant amount of weight, usually as body fat, particularly after age 40. The table below, from an article by Flegal and colleagues, illustrates this pattern quite clearly (). Obesity prevalence tends to be highest between ages 40-59 in men; and this has been happening since the 1960s, with the exception of the most recent period listed (1999-2000).

In the 1999-2000 period obesity prevalence in men peaked in the 60-74 age range. Why? With progress in medicine, it is likely that more obese people in that age range survived (however miserably) in the 1999-2000 period. Obesity prevalence overall tends to be highest between ages 40-74 in women, which is a wider range than in men. Keep in mind that women tend to also live longer than men.

Because age seems to be associated with obesity prevalence among urbanites, it would be reasonable to look for a factor that significantly increased survival rates as one of the main reasons for the steep increase in the prevalence of obesity in the USA in the 1980s. If significantly more people were surviving beyond age 40 in the 1980s and beyond, this would help explain the steep increase in obesity prevalence. People don’t die immediately after they become obese; obesity is a “disease” that first and foremost impairs quality of life for many years before it kills.

Now look at the graph below, from an article by Armstrong and colleagues (). It shows a significant decrease in mortality from infectious diseases in the USA since 1900, reaching a minimum point between 1950 and 1960 (possibly 1955), and remaining low afterwards. (The spike in 1918 is due to the influenza pandemic.) At the same time, mortality from non-infectious diseases remains relatively stable over the same period, leading to a similar decrease in overall mortality.

When proper treatment options are not available, infectious diseases kill disproportionately at ages 15 and under (). Someone who was 15 years old in the USA in 1955 would have been 40 years old in 1980, if he or she survived. Had this person been obese, this would have been just in time to contribute to the steep increase in obesity trends in the USA. This increase would be cumulative; if this person were to live to the age of 70, he or she would be contributing to the obesity statistics up to 2010.

Americans are clearly eating more, particularly highly palatable industrialized foods whose calorie-to-nutrient ratio is high. Americans are also less physically active. But one of the fundamental reasons for the sharp increase in obesity rates in the USA since the early 1980s is that Americans have been surviving beyond age 40 in significantly greater numbers.

This is due to the success of modern medicine and public health initiatives in dealing with infectious diseases.

PS: It is important to point out that this post is not about the increase in American obesity in general over the years, but rather about the sharp increase in obesity since the early 1980s. A few alternative hypotheses have been proposed in the comments section, of which one seems to have been favored by various readers: a significant increase in consumption of linoleic acid (not to be confused with linolenic acid) since the early 1980s.

What is the reason for this?

You may be tempted to point at increases in calorie intake and/or changes in macronutrient composition, but neither can explain this sharp increase in obesity in the 1980s. The differences in calorie intake and macronutrient composition are simply not large enough to fully account for such a steep increase. And the data is actually full of oddities.

For example, an article by Austin and colleagues (which ironically blames calorie consumption for the obesity epidemic) suggests that obese men in a NHANES (2005–2006) sample consumed only 2.2 percent more calories per day on average than normal weight men in a NHANES I (1971–1975) sample ().

So, what could be the main reason for the steep increase in obesity prevalence since the 1980s?

The first clue comes from an interesting observation. If you age-adjust obesity trends (by controlling for age), you end up with a much less steep increase. The steep increase in the graph above is based on raw, unadjusted numbers. There is a higher prevalence of obesity among older people (no surprise here). And older people are people that have survived longer than younger people. (Don’t be too quick to say “duh” just yet.)

This age-obesity connection also reflects an interesting difference between humans living “in the wild” and those who do not, which becomes more striking when we compare hunter-gatherers with modern urbanites. Adult hunter-gatherers, unlike modern urbanites, do not gain weight as they age; they actually lose weight (, ).

Modern urbanites gain a significant amount of weight, usually as body fat, particularly after age 40. The table below, from an article by Flegal and colleagues, illustrates this pattern quite clearly (). Obesity prevalence tends to be highest between ages 40-59 in men; and this has been happening since the 1960s, with the exception of the most recent period listed (1999-2000).

In the 1999-2000 period obesity prevalence in men peaked in the 60-74 age range. Why? With progress in medicine, it is likely that more obese people in that age range survived (however miserably) in the 1999-2000 period. Obesity prevalence overall tends to be highest between ages 40-74 in women, which is a wider range than in men. Keep in mind that women tend to also live longer than men.

Because age seems to be associated with obesity prevalence among urbanites, it would be reasonable to look for a factor that significantly increased survival rates as one of the main reasons for the steep increase in the prevalence of obesity in the USA in the 1980s. If significantly more people were surviving beyond age 40 in the 1980s and beyond, this would help explain the steep increase in obesity prevalence. People don’t die immediately after they become obese; obesity is a “disease” that first and foremost impairs quality of life for many years before it kills.

Now look at the graph below, from an article by Armstrong and colleagues (). It shows a significant decrease in mortality from infectious diseases in the USA since 1900, reaching a minimum point between 1950 and 1960 (possibly 1955), and remaining low afterwards. (The spike in 1918 is due to the influenza pandemic.) At the same time, mortality from non-infectious diseases remains relatively stable over the same period, leading to a similar decrease in overall mortality.

When proper treatment options are not available, infectious diseases kill disproportionately at ages 15 and under (). Someone who was 15 years old in the USA in 1955 would have been 40 years old in 1980, if he or she survived. Had this person been obese, this would have been just in time to contribute to the steep increase in obesity trends in the USA. This increase would be cumulative; if this person were to live to the age of 70, he or she would be contributing to the obesity statistics up to 2010.

Americans are clearly eating more, particularly highly palatable industrialized foods whose calorie-to-nutrient ratio is high. Americans are also less physically active. But one of the fundamental reasons for the sharp increase in obesity rates in the USA since the early 1980s is that Americans have been surviving beyond age 40 in significantly greater numbers.

This is due to the success of modern medicine and public health initiatives in dealing with infectious diseases.

PS: It is important to point out that this post is not about the increase in American obesity in general over the years, but rather about the sharp increase in obesity since the early 1980s. A few alternative hypotheses have been proposed in the comments section, of which one seems to have been favored by various readers: a significant increase in consumption of linoleic acid (not to be confused with linolenic acid) since the early 1980s.

Labels:

body fat,

calorie restriction,

energy expenditure,

obesity,

statistics

Sunday, January 17, 2021

Has COVID led to an increase in all-cause mortality? A look at US data from 2015 to 2020

Has COVID led to an increase in all-cause mortality? The figure below shows mortality data in the US for the 2015-2020 period. At the top chart are the absolute numbers of deaths per 1000 people. At the bottom are the annual change percentages, how much the absolute numbers have been changing from the previous years.

As you can see at the top chart the absolute numbers of deaths per 1000 people have been going up steadily, since 2015, at a rate of around 10 percent per year. This is due primarily to population ageing, which has been increasing in a very similar fashion. Since life expectancy has been generally stable in the US for the 2015-2020 period (), an increase in the number of deaths is to be expected due to population ageing.

What I mean by population ageing is an increase in the average age of the population due to an increase in the proportion of older individuals (e.g., aged 65 or more) in the population. In any population where there are no immortals, this population ageing phenomenon is normally expected to cause a higher number of deaths per 1000 people.

Now look at the bottom chart in the figure. It shows no increase in the rate of change from 2019 to 2020. This is not what you would expect if COVID had led to an increase in all-cause mortality in 2020. In fact, based on media reports, one would expect to see a visible spike in the rate of change for 2020. If these numbers are correct, we have to conclude that COVID has NOT led to an increase in all-cause mortality.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)